How splitting sound might lead to a new kind of quantum computer

Andrew N. Cleland, University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering

When you turn on a lamp to brighten a room, you are experiencing light energy transmitted as photons, which are small, discrete quantum packets of energy. These photons must obey the sometimes strange laws of quantum mechanics, which, for instance, dictate that photons are indivisible, but at the same time, allow a photon to be in two places at once.

Similar to the photons that make up beams of light, indivisible quantum particles called phonons make up a beam of sound. These particles emerge from the collective motion of quadrillions of atoms, much as a “stadium wave” in a sports arena is due to the motion of thousands of individual fans. When you listen to a song, you’re hearing a stream of these very small quantum particles.

Originally conceived to explain the heat capacities of solids, phonons are predicted to obey the same rules of quantum mechanics as photons. The technology to generate and detect individual phonons has, however, lagged behind that for photons.

That technology is only now being developed, in part by my research group at the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering at the University of Chicago. We are exploring the fundamental quantum properties of sound by splitting phonons in half and entangling them together.

My group’s fundamental research on phonons may one day allow researchers to build a new type of quantum computer, called a mechanical quantum computer.

Splitting sound with ‘bad’ mirrors

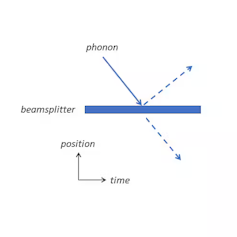

To explore the quantum properties of phonons, our team uses acoustic mirrors, which can direct beams of sound. Our latest experiments, published in a recent issue of Science, however, involve “bad” mirrors, called beam splitters, that reflect about half the sound sent toward them and let the other half through. Our team decided to explore what happens when we direct a phonon at a beam splitter.

As a phonon is indivisible; it cannot be split. Instead, after interacting with the beam splitter, the phonon ends up in what is called a “superposition state.” In this state the phonon is, somewhat paradoxically, both reflected and transmitted, and you’re equally likely to detect the phonon in either state. If you intervene and detect the phonon, half the time you will measure that it was reflected and half the time that it was transmitted; in a sense, the state is selected at random by the detector. Absent the detection process, the phonon will remain in the superposition state of being both transmitted and reflected. https://www.youtube.com/embed/UjaAxUO6-Uw?wmode=transparent&start=0 A brief Ted-Ed explainer on superposition, which happens when particles can exist in multiple places at once.

This superposition effect was observed many years ago with photons. Our results indicate that phonons have the same property.

Entangled phonons

After demonstrating that phonons can go into quantum superpositions just as photons do, my team asked a more complex question. We wanted to know what would happen if we sent two identical phonons into the beam splitter, one from each direction.

It turns out that each phonon will go into a similar superposition state of half-transmitted and half-reflected. But because of the physics of the beam splitter, if we time the phonons precisely, they will quantum-mechanically interfere with one another. What emerges is actually a superposition state of two phonons going one way and two phonons going the other – the two phonons are thus quantum-mechanically entangled.

In quantum entanglement, each phonon is in a superposition of reflected and transmitted, but the two phonons are locked together. This means detecting one phonon as having been transmitted or reflected forces the other phonon to be in the same state.

So, if you detect, you’ll always detect two phonons, going one way or the other, never one phonon going each way. This same effect for light, the combination of superposition and interference of two photons, is called the Hong-Ou-Mandel effect, after the three physicists who first predicted and observed it in 1987. Now, my group has demonstrated this effect with sound.

The future of quantum computing

These results suggest that it may now be possible to build a mechanical quantum computer using phonons. There are continuing efforts to build optical quantum computers that require only the emission, detection and interference of single photons. These are in parallel with efforts to build electrical quantum computers, which through the use of large numbers of entangled particles promise an exponential speedup for certain problems, such as factoring large numbers or simulating quantum systems.

A quantum computer using phonons could be very compact and self-contained, built entirely on a chip similar to that of a laptop computer’s processor. Its small size could make it easier to implement and use, if researchers can further expand and improve phonon-based technologies.

My group’s experiments with phonons use qubits – the same technology that powers electronic quantum computers – which means that as the technology for phonons catches up, there’s the potential to integrate phonon-based computers with electronic quantum computers. Doing so could yield new, potentially unique computational abilities.

Andrew N. Cleland, Professor of Molecular Engineering Innovation and Enterprise, University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.