Being bombarded with delivery and post office text scams? Here’s why — and what can be done

Ismini Vasileiou, De Montfort University and Paul Haskell-Dowland, Edith Cowan University

For most people, the ping of an incoming SMS will induce some level of excitement — or mild intrigue at least. But with SMS scams on the rise, many may now be meeting this same sound with trepidation.

According to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission’s (ACCC) ScamWatch website, scams delivered via “phone” or “text” this year far outnumber those sent through any other delivery method, including social media or email.

Delivery and postal scams are particularly common in SMS scam campaigns, with Australia Post even hosting a dedicated scam alerts page on its website. Other forms of fraud encountered via SMS include premium-rate text fraud, tax demands, fake contact-tracing messages and smishing (SMS phishing).

While eliminating the threat might be difficult, there are some simple ways you can avoid becoming the next victim.

A growing global problem

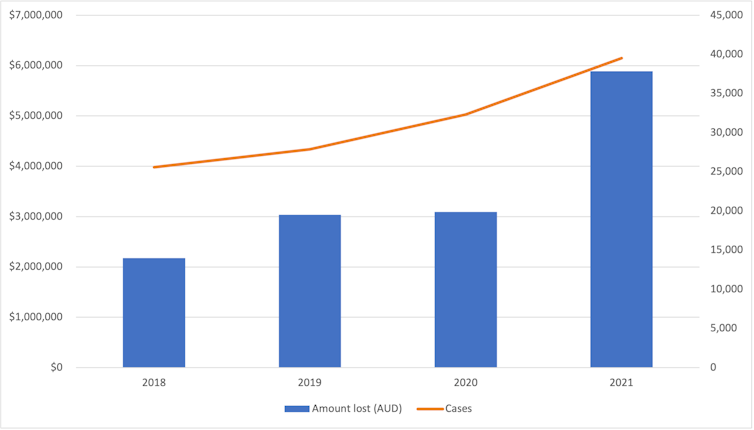

SMS scams have seen considerable growth in the last few years. ScamWatch reported a near-doubling of yearly losses between last year (A$3,091,790 lost) and this year, as of August (A$5,889,596). SMS scam reports have also shot up to a total 39,531 reports this year as of August — up from last year’s total of 32,337.

Of particular concern is the escalation in cost per incident (total reported losses divided by number of incidents), indicating a significant shift in the impact of these scams.

This isn’t just in Australia, either. The US Federal Trade Commission reported US$86m in losses to SMS scams last year, and the UK’s Office of Communications reported a significant rise in scam messages received by UK residents.

Read more: Why are there so many text scams all of a sudden?

Evolving scam techniques

Email remains the cheapest method to distribute scams. But most email services now provide efficient spam filters to block them.

When it comes to SMS messages, however, our smartphones don’t afford the same level of protection. While telecommunication providers are enhancing their SMS scam (and spam) detection capabilities, this issue so far hasn’t received the same attention as email scam.

Perhaps this is because of the extent of impact on consumers. Compared with email scams, it was only relatively recently that SMS scams became a problem leading to direct and highly visible financial consequences. https://www.youtube.com/embed/7h_tRig3vEw?wmode=transparent&start=0 Australia Post has provided guidance on avoiding postal scams targeting Australian’s.

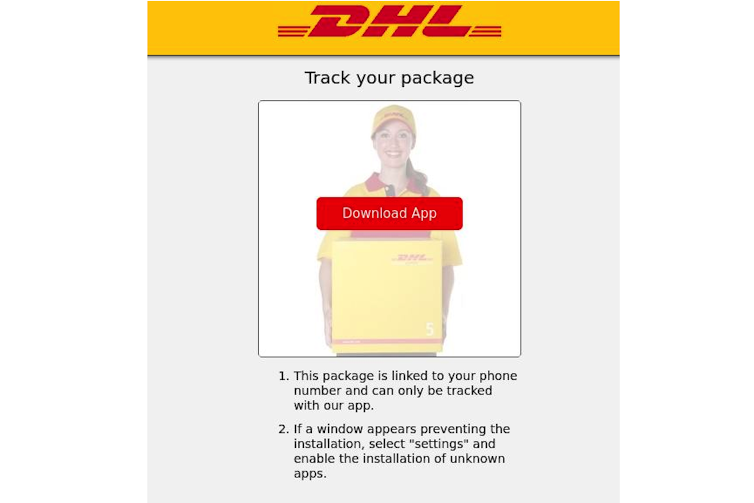

That said, SMS scams aren’t just limited to financial fraud. Since last month, Australian’s have been increasingly targeted with SMS messages carrying the flubot malware. This malicious software (malware) migrated from Europe to Australia, and targets Android devices with the intention of stealing online banking credentials.

It’s delivered via SMS messages that attempt to convince the recipient they must install an “app” on their smartphone to reschedule a missed delivery or listen to a fake voicemail. Unfortunately, rather than an actual app downloaded from the app store, this fake “app” contains malware which is installed when the link in the SMS message is clicked.

Once installed, the malware provides “overlays” (fake pages) on top of the login screens of genuine banking apps installed on the phone. So the next time the victim uses their real banking app, the overlays capture their banking details, which are then fed back to servers controlled by cyber criminals. https://www.youtube.com/embed/3uz1RcKTpQM?wmode=transparent&start=0 This video shows the flubot overlay on an online banking app.

The flubot malware was previously associated with the Cabassous cybercrime group in 2020, but seems to have seen a resurgence in 2021 despite multiple arrests in Spain.

Why SMS scams are hard to stop

Scammers often leverage real scenarios to mislead people. The COVID pandemic has forced people to work from home, take temporary leave, or get laid off altogether — prompting a surge in online shopping and more internet use overall.

Read more: Why are there so many text scams all of a sudden?

Scammers are taking advantage. The ACCC’s ScamWatch received 13,191 “online shopping scam” reports this year as of last month — with 35.6% of the reports claiming financial loss.

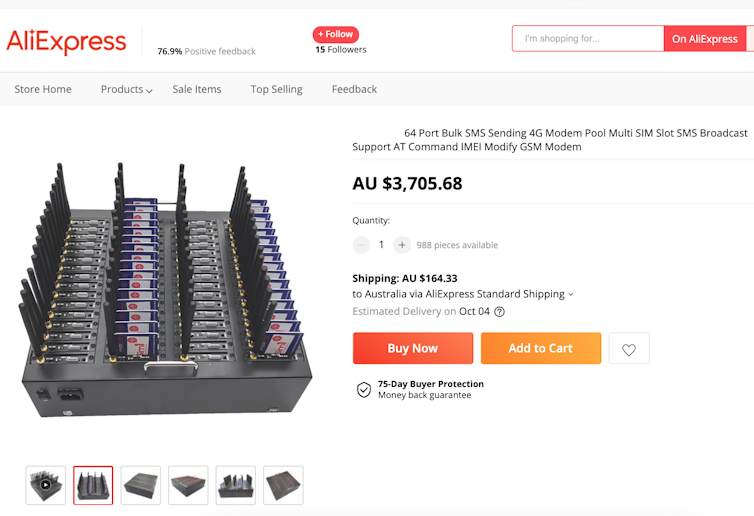

Most malicious campaigns use a scatter-gun approach, targeting thousands of phone numbers sequentially (such as by starting with “0400 000 000” and working up), randomly (with the aim of seeming less predicatable), or using stolen lists of valid numbers.

And while most mobile devices do have options to block or filter numbers, such as by SMS filtering services or by categorising unknown numbers — much like email scam/spam filters these approaches are only as reliable as data collected from user reports.

If all scam messages came from a single number, it would be a simple case of blocking that number. Unfortunately, scammers use sophisticated technology to rapidly send large volumes of SMS messages, and will often generate spoofed numbers to appear legitimate or to bypass blocking by the phone’s automatic filter, or the user themselves.

Since the scam messages are not expected to generate replies (since they only want you to click the link), they don’t even need to be real phone numbers. On the screen they may appear legitimate (such as with “DHL” appearing as the company name) or may be completely random.

It’s evident blocking is only part of the full solution. Ideally the criminal groups behind these operations would be shut down. But as with most forms of organised crime, the culprits are often located overseas — making it difficult to investigate and prosecute for these crimes.

Exercise caution

Spotting scams is becoming increasingly difficult. Scammers use various techniques to trick targets, including:

- pretending they have authority. For example, by pretending to be DHL or the tax office

- convincing you there is limited time to respond. This can prompt panic and an urgency to respond

- offering something of value or attraction to incite a response, such as a fake lottery win. Or threatening you with a consequence, such as a fake a penalty or fine.

Legitimate organisations and agencies will rarely (if ever) use overly casual, hostile or threatening language in an SMS. To stay safe and alert, you must keep this in mind.

If you ever receive a suspicious SMS message, don’t reply or click on any attached links. If the message purports to come from an official organisation, always contact the organisation directly (never trust any contact details included in the message).

If your phone supports the option, block the number — and consider reporting it to the Australian Communications and Media Authority.

If you’ve been compromised (or suspect it)

If you think you have fallen victim to a scam, it’s important to remain calm.

The first thing to do is seek advice from the relevant organisation, which in Australia is ScamWatch. If you’re concerned your banking details may have been compromised, contact your bank immediately to block any rogue transactions, prevent future transfers and change your details as necessary.

If you have disclosed your password, you must change it immediately across all sites and services the password is used for. And if the issue is affecting a work-related device, contact your IT department to check whether your device has been compromised. This may require it to be checked for malware, cleaned and/or re-imaged.

Finally, always ensure your mobile devices are kept up-to-date with patches and software upgrades. While this might not stop the SMS messages, you will benefit from system updates designed to protect you. The Australian Cyber Security Centre has further advice on what to do if you’ve fallen victim to a scam.

Ismini Vasileiou, Associate Professor in Information Systems, De Montfort University and Paul Haskell-Dowland, Associate Dean (Computing and Security), Edith Cowan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Photo by Rodion Kutsaev on Unsplash